Science & Discovery| Sienna Ray

You know the look. It’s the glassy-eyed stare your partner gets when he’s sitting on the couch, seemingly comatose. You ask, “What are you thinking about?” and he replies, with terrifying sincerity, “Nothing.”

You don’t believe him. How can a human brain be doing nothing?

For decades, we’ve treated these moments as relationship quirks or communication failures. But what if I told you that his brain is actually performing a prehistoric function? What if his “zoning out” is a biological feature, not a bug, hardwired by thousands of years of hunting in silence? And conversely, what if your ability to find the ketchup in the fridge—when he swears it’s not there—isn’t magic, but a superpower gifted by your gatherer ancestors?

New perspectives in evolutionary psychology are connecting the dots between our modern arguments and our ancient survival needs. From the “Nothing Box” to the width of our visual field, the hardware running our minds might be much older than we think.

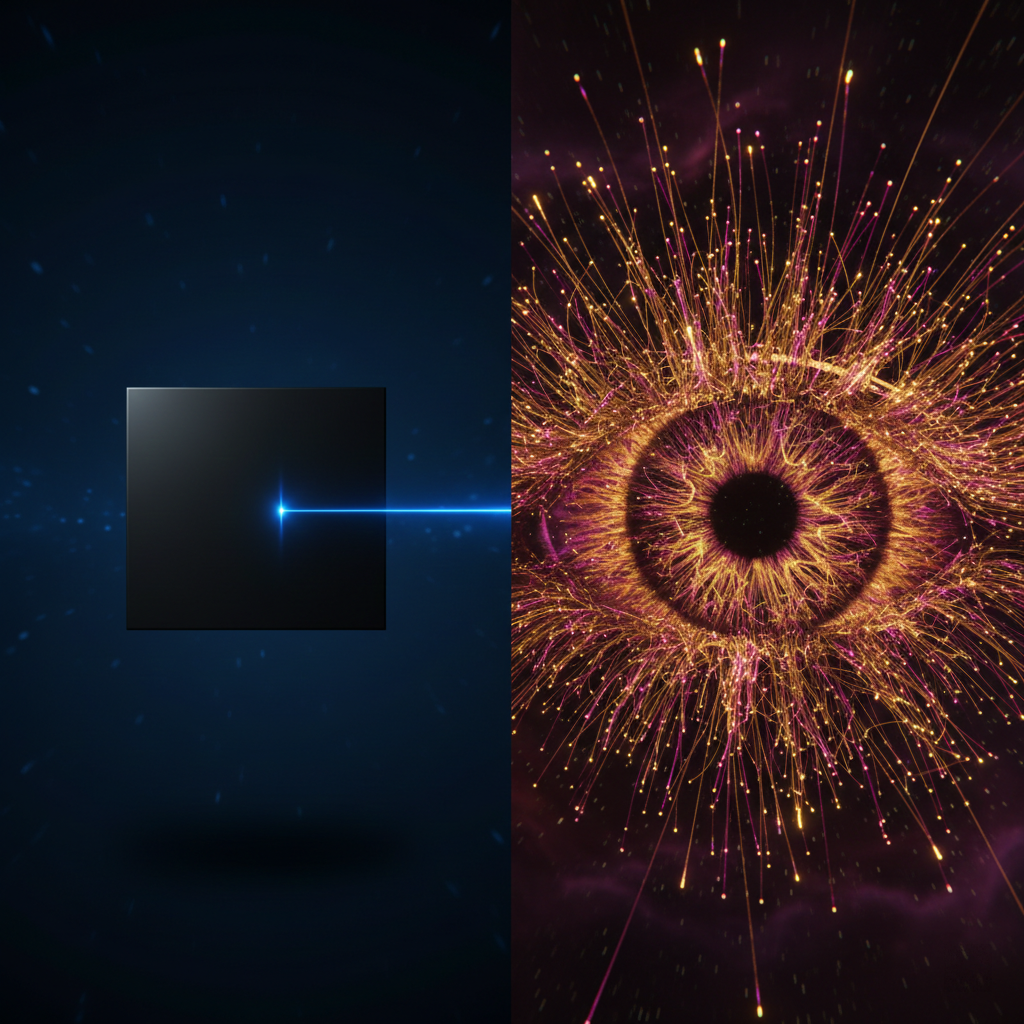

Deep Dive: The Radar vs. The Laser

The most immediate difference often cited in evolutionary circles is visual perception. While modern neuroscience shows our eyes are anatomically similar, the processing of visual data seems to follow distinct evolutionary paths. Research suggests that the male brain, shaped by the needs of the hunter, prioritizes tunnel vision. This isn’t just a metaphor; it’s a focus mechanism. When tracking a moving target (a deer then, a terrifying merge on the highway now), the brain suppresses peripheral distractions to lock onto coordinates and velocity.

In contrast, the female brain is often described as possessing a radar system—a wide-angle lens capable of monitoring a 120-degree arc. In the ancestral environment, a “gatherer” didn’t just look for berries; she had to spot the subtle red of a ripe fruit against green foliage while simultaneously monitoring a child playing five feet away and scanning for predators in the periphery. This explains the classic domestic mystery: why he can’t see the butter unless it’s front-and-center, while you can spot it behind the milk jug without turning your head. It’s not laziness; it’s a difference in field-of-view processing designed for survival.

The Audio Insight: Boxes and Wires

Deep diving into the source material, we find a fascinating breakdown of how this “hardware” influences our internal processing. The concept of the “Nothing Box” is validated here as a crucial coping mechanism for the male brain.

According to the audio analysis, the male brain is compartmentalized into “boxes”. There is a box for the car, a box for the job, a box for the kids. Crucially, these boxes do not touch. When a man is in his “Work Box,” he is physically incapable of seeing the “Relationship Box.” But the ultimate sanctuary is the Nothing Box—a mental space where he can sit, completely brain-dead, and recharge. It’s the evolutionary equivalent of sitting motionless in a blind, waiting for prey.

On the flip side, the female brain is described as a massive ball of wire where “everything is connected to everything”. Emotion links the car to the job, which links to the kids, which links to what his mother said three years ago. This is why women are often better at multitasking and emotional reading—because their neural pathways are constantly cross-referencing data. The audio notes that women can read facial micro-expressions (a skill honed by pre-verbal communication with infants) far better than men, who rely on verbal data.

The Origins of Art: Poetry vs. The Hunt

Perhaps the most poetic theory emerging from this analysis is the gendered origin of art itself. We often assume storytelling is a universal human trait, but the source suggests a divergence in form.

The theory proposes that Storytelling is a male invention, born from the post-hunt debrief. Picture it: the hunters return to the fire, adrenaline pumping. They need to recount the strategy, the danger, and the kill to the tribe. This narrative style is linear, goal-oriented, and action-driven—the blockbuster movie of the Paleolithic era.

Poetry, however, may be the creation of the female mind. Rooted in the rhythm of lullabies used to soothe infants and the chants used in healing rituals, poetry is less about “what happened” and more about “how it feels.” It is the language of emotion, healing, and connection. While men were documenting the external world of the hunt, women were mapping the internal world of the human experience.

Next time you catch him staring at a wall, don’t ask what he’s thinking. Just hand him a snack—he’s technically “hunting” in his Nothing Box. Subscribe to Spherita for more deep dives into the science of us.